In this article, I’m sharing research findings on false beliefs that still hinder startup business development.

The research confirmed 98.5% successful startups had to do major pivots on the go. They were already in the market and had to modify their product or service, to redefine their target customer, to find new ways of using their product, to change the pricing or distribution strategy.

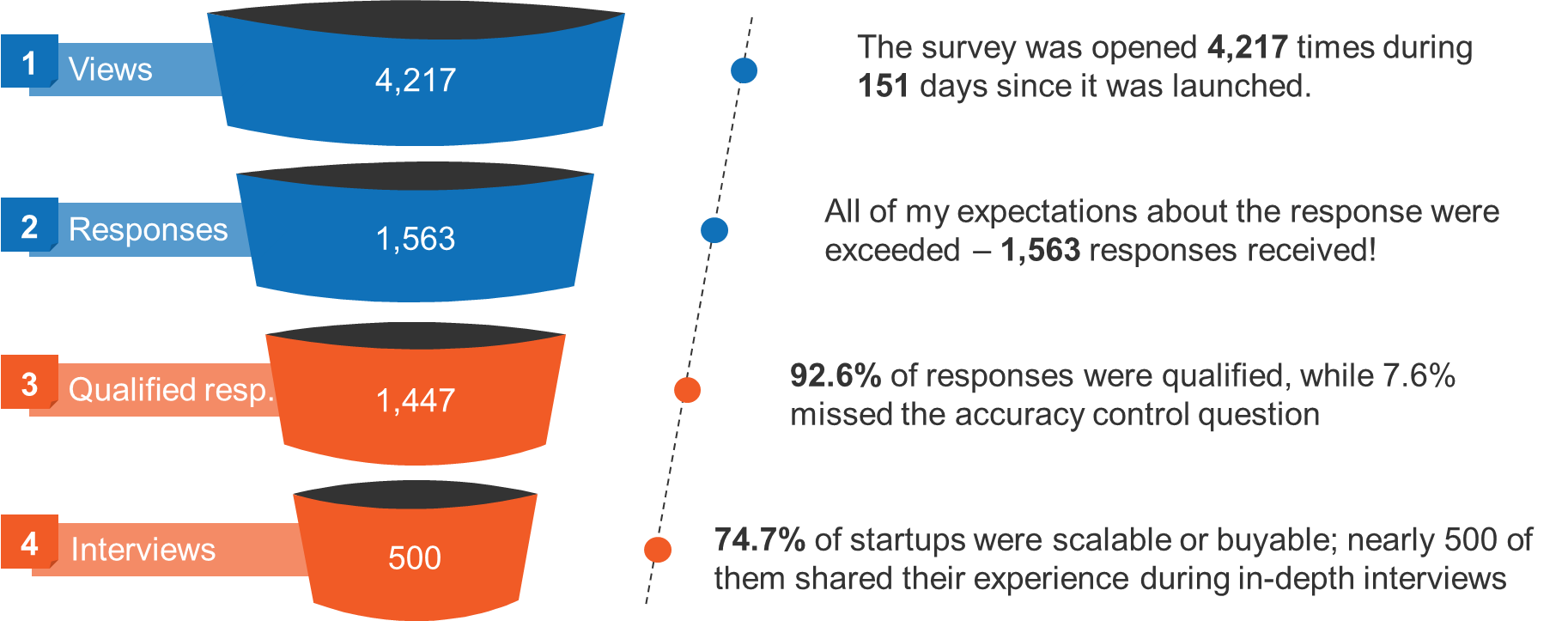

The survey received 1,563 responses from startup founders from all around the world and 1,447 were qualified. I also conducted nearly 500 in-depth interviews with startups that fell under the category of buyable or scalable startups. According to definition of startups, not every new business is a true startup. Therefore, my analysis was focused on startups that fell under the category of scalable or buyable startups (1,081 qualified responses or 74.7%).

I was not seeking to do research to precisely represent the startup community structure worldwide, but was focused on collecting responses from early stage startups in different regions and different industries which allowed me to compare their specifics and possible interdependencies.

Many startups are talking about word of mouth advertising and hoping for viral growth. But viral effect happens very rarely, especially if there is no consistent, targeted action from the startup. So, how can the chances increas? How can startups make their product or brand go viral?

My global research showed that 78.9% of the startups had already launched their products and more than two-thirds of startup founders (67.5%) wanted help with scaling their business. But only 10.6% of all startups had prepared marketing material to support their viral growth.

That means that 9 out of 10 startups don’t have their marketing material ready for viral growth but they expect a miracle to happen! Why? There is a simple explanation. Most startups don’t know what to do or how to do it effectively.

More than a third (34.2%) of startups, that already have found product-market fit and some traction, still don’t know what growth engines are or how to employ them, even though they were introduced by Eric Ries in 2011. Before spending major budget on promotions, it would be wise to focus on one or more of these growth engines:

My in-depth interviews with the global startups showed that most founders have already checked or were preparing to check hypotheses related to distribution and communication channels (46.2%), cost and revenue model (41.3%), and competitive advantage (39.6%). But the remaining startups were counting just on assumptions.

It is normal to build your startup business model on assumptions initially. But at least most of your assumptions should be replaced with solid facts during the feasibility study. Decide what type of engagement and how much data you need to check your hypotheses. Ask yourself what insights or assumptions need to be checked to move forward. Then think about the simplest test you could use to check it.

Too many startups still count on big launches. 46.2% of startups expected that a big launch will help them, even though they were yet to find significant traction in the market. Traditional businesses often do big launches and implement expensive market entry strategies because it’s more or less certain to have a positive payback. Sometimes, even small businesses conduct big launches with good results. But startups are not traditional businesses.

In early 2009, Sean Ellis (2009) shared the fact that more than 80% of startup big launches fail and nothing has essentially changed since then. Startups are being built on assumptions which first must be tested in the market. It’s crazy to count on a big launch until you have at least found your product-market fit, identified your ideal clients (early adopter-evangelists), and tested your marketing communication (messages and channels). Most startup launches fail for a few reasons: wrong product, wrong target customers, wrong value proposition, wrong communication channel, or even errors in the whole process.

Once the main competitors are identified and their core offers analyzed, it’s time to identify indirect competitors. My global research on startups revealed that more than 42% of early stage startups didn’t analyze their indirect competitors, which was a huge mistake for most of them because their value proposition was built on the wrong assumptions without analyzing the full picture.

For the indirect competitive analysis, you need to think a bit outside the box. How else can the same problem be solved or the gain realized? Have in mind that the old way of solving the same problem is your competitor also. Look at the big picture of the situation. Maybe there are solutions that cost no money at all, but customers must put more effort and time? Maybe there are alternatives that make the particular problem unimportant? Maybe there are some circumstances where the customer won’t be willing to solve the problem at all?

Most startups focus on product development, growth, fundraising, and achieving another product development milestone. Profit mostly takes on a lower priority and becomes something to be taken care of later when significant growth is achieved. But this is a very irresponsible attitude! More than 53.1% of the startups I surveyed didn’t focus on profit at all: 16.1% didn’t know anything about profit hacking or how to do it and another 37% didn’t think it was important for them.

Only 34.7% of startups have adopted and were constantly working on solutions to improve their profit. By contrast, those startups that were focused on profit from the very beginning have achieved much greater success in the market by every measure: accumulated investments, business growth, and profit, of course!

More findings and practical step by step advice is published in the book Startup Evolution Curve: From Idea to Profitable and Scalable Business. To find out more about Donatas, click on the interview here.

Cover photo: Takahiro Sakamoto on Unsplash